December 21, 2011

Kartina Richardson

Pasolini’s Accatone

**Update: Accatone is a pain in the ass to see, but it’s on youtube right now. Great quality in one full video. Watch it before it vanishes (make sure to turn on CC)**

Ballila the Fat Thief to Accatone the Starving Pimp:

Did you sell your car? Is all the gold gone? You really look like a beggar. What a bad end!

Hai venduto la macchina? E finito l’oro? Ma tu mi pari proprio un dizgrazato. Che brutta fine!

Che brutta fine! Che brutta fine!

I watched Accatone for the first time eight years ago, and for eight years now I’ve recited those words “Che brutta fine!” with regular regularity. I say them out loud, not to myself, and I do this the most as I walk from one place to another. These days I walk two miles to the coffee shop and two miles back. This allows me thirty three minutes twice a day to call upon “Che brutta fine.” It is a compulsive and calming habit, like chewing a piece of hair, or fondling the edge of t-shirt. Eva D’Andrea my oldest friend, will attest to this routine. She is an Italian just back from Italy and I especially enjoy saying the sentence around her. It is more authentic with an Italian around. Che brutta fine! The rolling R thrills my tongue.

But behind the seduction of certain phonetics, lies the other reason. The larger, less cheerful explanation behind my attraction to these words and why my mind returns to Accatone repeatedly: My soul, or a portion of it I have yet to resolve, is Accatone’s posture embodied. Shoulders hunched, head down, he stands heavy with the weight of his own immorality.

I think of Accatone with increasing frequency at the end of the warmer months. Summer is the season of debauchery, and I have sinful proclivities. When the lights come up at a nightclub, a noisy crowd turns suddenly sheepish; such is the case with summer’s end. As August passes, guilt, or worse, guilt’s absence, is left in its wake. No time then is more appropriate to watch Accatone.

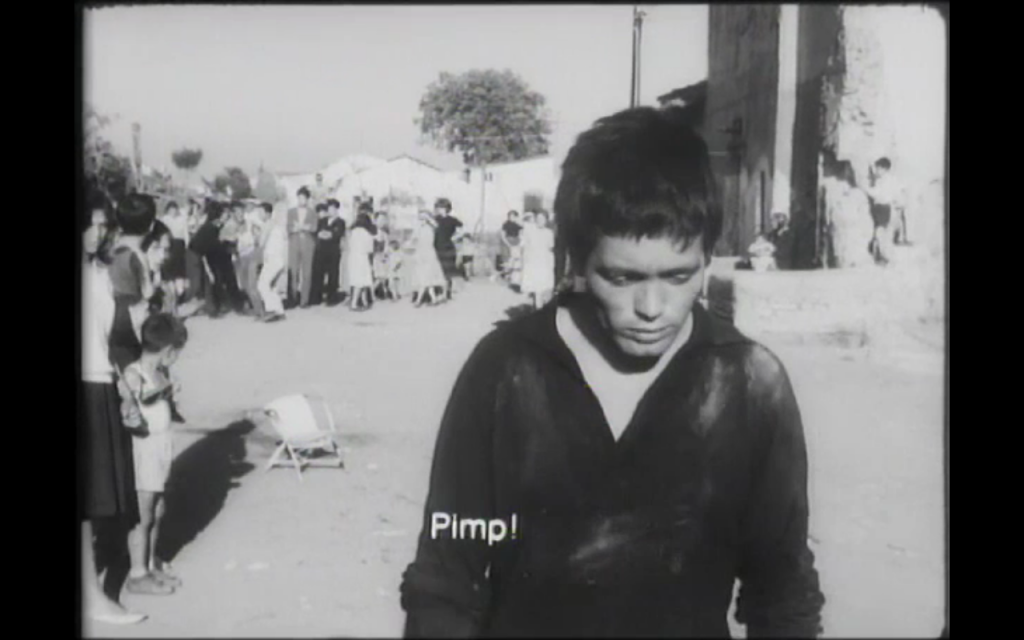

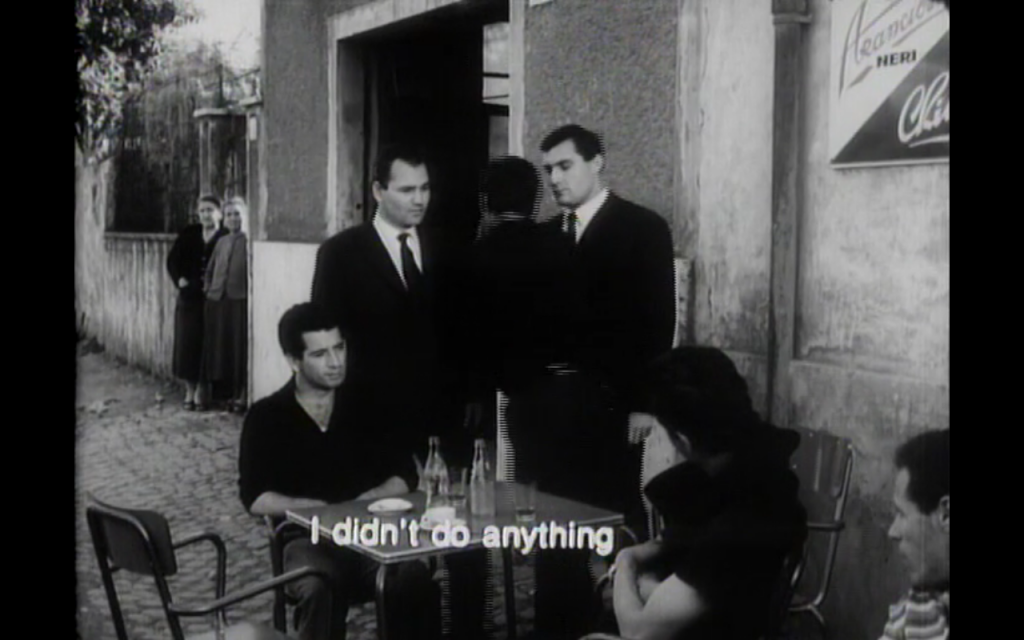

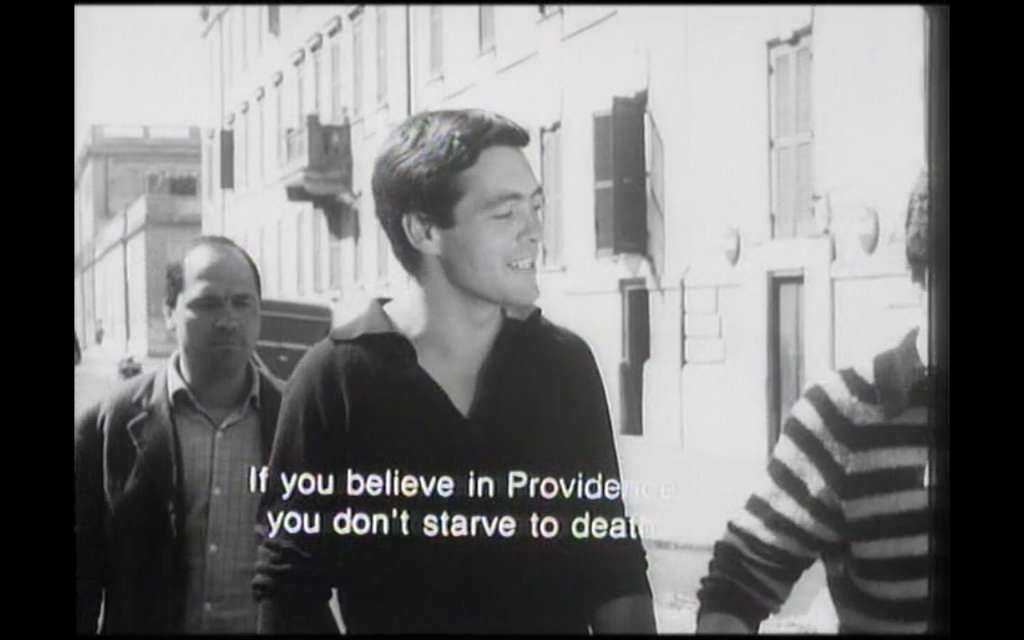

In Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1961 film (his first), Franco Citti plays Vittorio, aka, Accatone, a pimp and hopeless bum. When his prostitute/girlfriend Maddalena is jailed, Accatone finds himself free of a woman he despises, but also without a source of income.

Work however, is not an option.

The criminal life is one of uncertainty and danger, but legitimate work for the poor is grueling, the sole benefit of which is honor. This is an integrity laughable to Accatone. What good is honor if the world itself is not just?

War destroys, men starve, and a person as monstrous as himself is allowed to operate. If this is God’s work, God himself must be corrupt. It is in fact the dread of this corruption that drives Accatone to do his scandalous doings.

This is where our affection for Accatone truly begins, for we see he is sad and not bad.

Accatone: Who’ll bet all we’ve drunk tonight that I’ll jump off the bridge.

Short pimp: And die like Tosca!

Accatone: Don’t believe me? Then bet! Clowns. And with my clothes on!

Dancing pimp: Don’t go too far.

Accatone wants to believe in goodness, in an idea of heavenly justice, but life offers him only evidence to the contrary. Each one of his bets then, can be seen as a twisted means of giving God a chance to redeem himself and punish a cocky, sinful, man. The absence of punishment however, means there is no heavenly justice, and if there is no heavenly justice then there is no point in striving for a morality that is now meaningless.

…And so Accatone continues to steal and pimp because nothing physically prevents him from doing so. No hand from heaven holds him back.

One scene in particular illustrates this tension between the physical reality of life and the metaphysical realm of religion and morality; each world making absurd the other: Accatone and his poor friends, faint with hunger, convince Scucchia, their only pal with a real job, to let them cook spaghetti on his stove.

While they wait for the pasta to finish, Accatone takes Scucchia aside:

Accatone: Are you game to screw them?

Scucchia: What for?

Accatone: Theres eight of us for two pounds of spaghetti.

Scucchia: How can we get rid of them?

Accatone: It’s nothing. You insult us. Call us bums, good for nothings. It’s an offense to our honor! I’ll take care of them. They’ll leave, and we eat the pasta!

Accatone’s plan works and the stupid pimps leave.

But who is right? Should a starving man eat though insulted, or leave hungry and honorable? To which realm do we pledge our allegiance when each argues convincingly for top priority?

This struggle between the actual and abstract is shown beautifully in the camera work, and this is also where Accatone’s influence on Scorsese is most evident. Neo-realist in mood and story, it is a gritty, textured, film whose characters struggle to survive in poverty. Supporting scenes of daily life however, is camera work that evokes something larger. The importance of story, acting, lighting, sound etc, isn’t to be diminished, but the heart of film’s potential to express the transcendent truly lies in the movement of the camera. This is why Tarkovsky is the master of the cinema (let the fighting begin!). In each of the shots in the video above, we are aware of the divine amidst the hard and real.

But, the holy and earthly are an unhappy union, and hosting this eternal battle is wearisome. I suspect Accatone would find solace here:

Ave Maria Gratia Plena

Was this His coming! I had hoped to see

A scene of wondrous glory, as was told

Of some great God who in a rain of gold

Broke open bars and fell on Danae:

Or a dread vision as when Semele

Sickening for love and unappeased desire

Prayed to see God’s clear body, and the fire

Caught her brown limbs and slew her utterly:

With such glad dreams I sought this holy place,

And now with wondering eyes and heart I stand

Before this supreme mystery of Love:

Some kneeling girl with passionless pale face,

An angel with a lily in his hand,

And over both the white wings of a Dove.

– Oscar Wilde

Though Accatone’s desperation over God’s apparent leniency is real, it is also a very convenient excuse to deny the possibility of goodness, thereby thwarting any serious attempt at personal responsibility. This cycle of self-loathing/god-challenging so continues uninterrupted until he meets Stella, a blonde and cherubic suggestion that virtue does indeed exist.

Stella is a working girl. She gives all her earnings to her parents, owns one dress, and is ignorant to the world of pimps and hookers. As integrity is all she has, Stella adheres tirelessly, but not loudly, to ideas of rectitude.

Naturally the two get together. But as falling in love is too ridiculous a process for the Roman slums, Stella and Accatone’s shared affection is more agreement than organic blossoming.

Now, anyone acquainted with the daily routine of self loathing can describe the unhappy duty of receiving a loved one’s gaze. The affection is returned, because the self loathing do love others, but accompanying affection is the great shame; a tremendous sorrow that the one you love has the misfortune of loving you. In turn, this shame provokes two contradictory but simultaneous urges; to change the nature of your evil ways and to corrupt the integrity that’s provoked self-reflection. Because the desire to destroy goodness is unconscious in all but the most villainous, when Accatone decides to pimp a compliant Stella out, he believes he does so for money and the protection of his pimply reputation.

…In reality however, he’s testing the strength of a purity that emasculates him in comparison.

When Stella’s virtue proves impenetrable…

Accatone recognizes his trespass.

Expecting to face Stella’s indignation, he meets only despair and frailty in its place.

Receiving sadness in the place of expected anger unnerves with powerful swiftness. This is exceptionally true if you lean towards self righteousness. Moved by this interaction, Accatone makes a very brief, but very valiant effort to join the squares and go the straight and narrow.

It’s easy to call Accatone lazy, but lost in our initial repulsion to his attitude is the fact that he is right.

It is grueling work, and it is unfair that living should be so difficult.

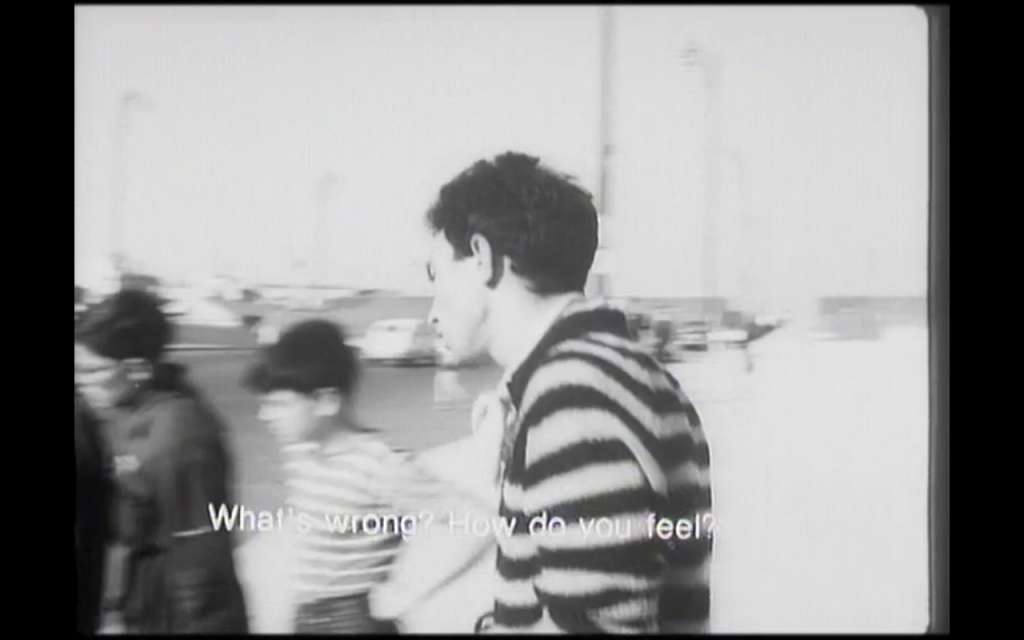

Stella: Vittorio what’s happened!

Accatone: I’m a dope that’s what’s happened! For 1000 lousy lire I went and killed myself. I should of had a stroke instead of going there.

Stella: Calm down, don’t say that. Listen, let me say something.

Accatone: Skip it, forget it.

Stella: Vittorio if you aren’t up to working, I’m ready to go on the street again, if that’s better.

Accatone: What are you saying? Shut up.

Stella: What do you care about me? No one’s going to cry over me.

Accatone: You on the street? Cut it out. I’ll look after you. You’ll stay home. If I decide something that’s it. Either the world kills me or I kill it!

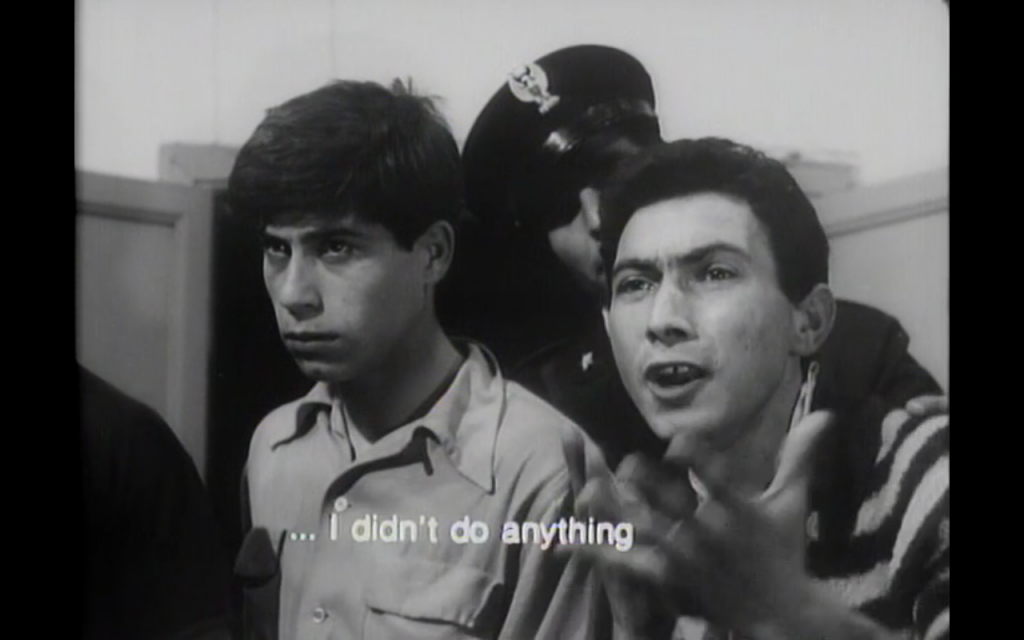

At the same time however, Maddalena, Accatone’s jailed prostitute, made wise to his new relationship with Stella, takes revenge on her unfaithful pimp and reports him to the police. This unhappy turn of events brings us to the final scene, e che brutta fine, che brutta fine!

Exhausted after one day of work, Accatone reverts to his ways and joins his friends on the hunt.

Accatone: I don’t have a cent, and I tried working

Balilla: Shame on you!

Accatone: What’ll we do?

Balilla: The world belongs to those with teeth.

Accatone: Who do we hit?

Balilla: Why don’t we do like rififi? We just trust to luck.

After hours of searching the men happen upon an unmanned truck full of salami. They steal the meat, and go on their cocky way.

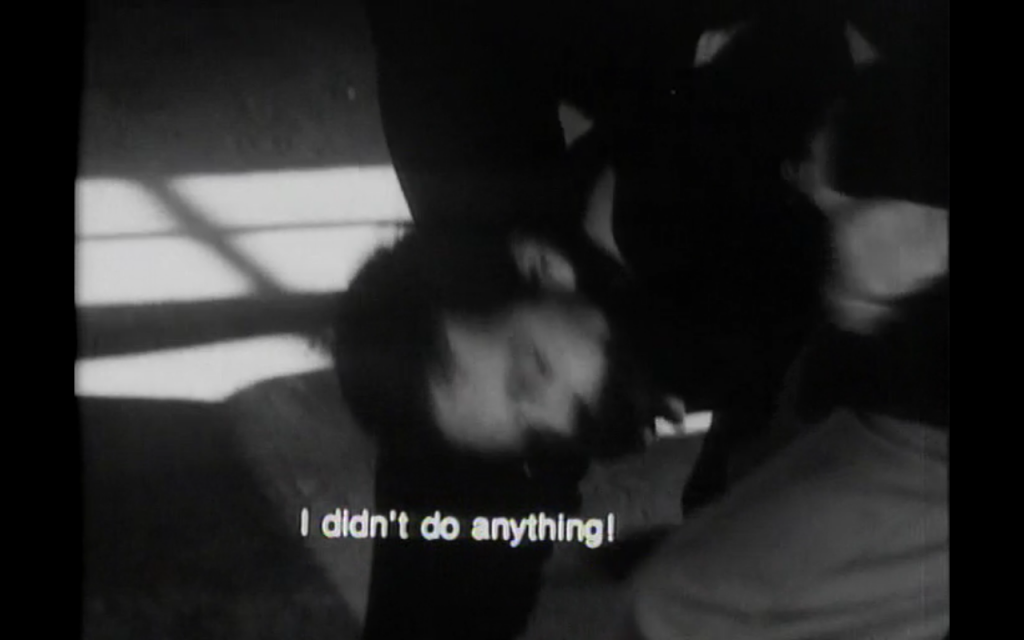

Watching the theft however, are the police, now with cause for arrest. They stop the men, but Accatone runs!

Stealing a motorbike, he races down the street and veers around a corner!

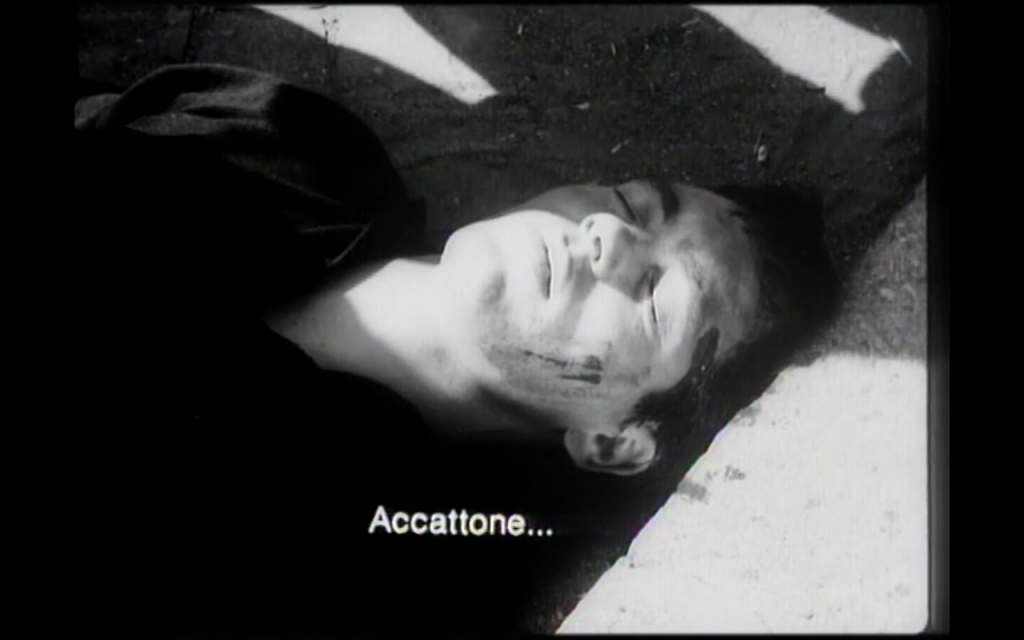

Moments later the screech of tires, a loud crash, and a woman’s scream tell us his bloody fate.

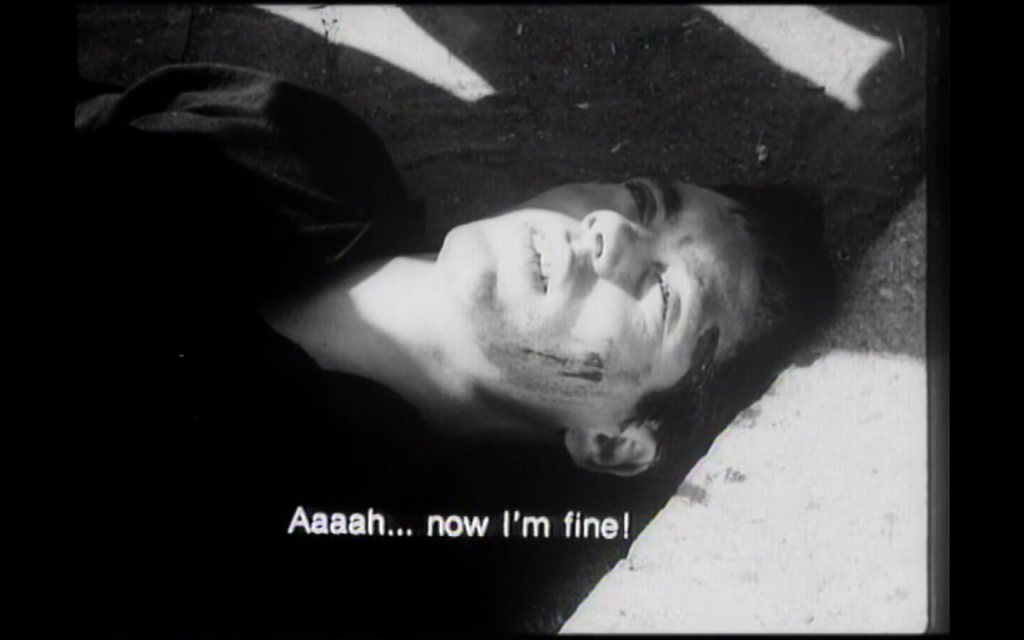

As children misbehave to get an adult’s attention, so does Accatone to feel the lord’s wrath. After repeated provocation, God has finally shown his muscle. There is some justice in the world. There is some order. There is some something.

This then is the ultimate comfort and Accatone is finally at peace, for if God kills you, you’re dead, but at least now you know he’s watching.

Accatone: Aaaah… Now I’m fine!

• like this post? subscribe to the Mirror RSS Feed •

“Accatone” is a radical work because it is about a bourgeois intellectual who identifies with “the lowest of the low” The film does not “visit” the poor as Neo-realism did. it is entirely enegaged with their lives. This is why “Accatone” was attacked on its release, and every subsequent Pasolini film likewise.

Franco Citti, my favorite actor. If only we had other Pasolinis capable of finding more Cittis. Though it is no doubt unfair, and pointless, whenever I see a contemporary actor try to find some grit in a character, some kind of vital energy beyond the surface tricks of the trade, I always compare them to Citti and I almost always find them lacking. There’s something he has that is so powerful, unadulterated, and the shortcomings of the amateur don’t seem to tarnish his on screen presence.